This summer, the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, the foundation running most of

Berlin’s museums, commisioned me to photograph the new issue of their biannual

magazine, focusing on the restitution of art confiscated during the Third Reich. A

seemingly dry assignment, which turned out to be an exciting look behind the scenes of

cultural institutions and a moving encounter with the fates of those affected by persecution

and expropriation under the Nazi regime. And while those crimes were commited more

than 70 years ago, the injustice lives on to this day, I also got to witness story of those

trying to rectify it and the obstacles they face.

Pictured are five of many books that the Freemasons in Potsdam were forced to “donate”

to the Berlin museums when they succumbed to the pressure to cease their

operations. Returned together with 379 other books in 2016, after systematic

research within the catalogue of the Staatsbibliothek.

This summer, the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, the foundation running most of

Berlin’s museums, commisioned me to photograph the new issue of their biannual

magazine, focusing on the restitution of art confiscated during the Third Reich. A

seemingly dry assignment, which turned out to be an exciting look behind the scenes of

cultural institutions and a moving encounter with the fates of those affected by persecution

and expropriation under the Nazi regime. And while those crimes were commited more

than 70 years ago, the injustice lives on to this day, I also got to witness story of those

trying to rectify it and the obstacles they face.

Pictured are five of many books that the Freemasons in Potsdam were forced to “donate”

to the Berlin museums when they succumbed to the pressure to cease their

operations. Returned together with 379 other books in 2016, after systematic

research within the catalogue of the Staatsbibliothek. August Gaul’s “Lying Lion”, commissioned by

Jewish publisher Rudolf Mosse, was part of the

extensive art collection his son was forced to

surrender for permission for him and his family

to leave Germany. It was restituted to the heirs in

2015.

August Gaul’s “Lying Lion”, commissioned by

Jewish publisher Rudolf Mosse, was part of the

extensive art collection his son was forced to

surrender for permission for him and his family

to leave Germany. It was restituted to the heirs in

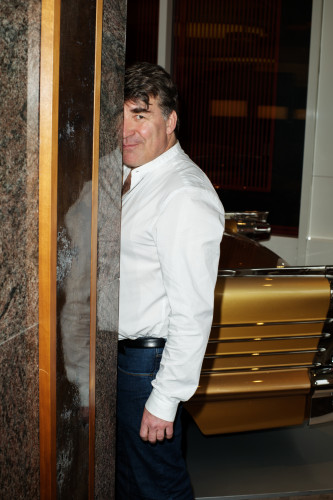

2015. Stuart E. Eizenstat was instrumental in negotiating the Washington Principles, a binding,

multinational treaty to research and return art identified as confiscated by the Nazis. He’s

now working as an attorney in Washington, D.C., where I photographed him in his office.

Stuart E. Eizenstat was instrumental in negotiating the Washington Principles, a binding,

multinational treaty to research and return art identified as confiscated by the Nazis. He’s

now working as an attorney in Washington, D.C., where I photographed him in his office. Mr Eizenstat was serving as Ambassador to the

European Union when he was negotiating the

treaty in 1998, leading to thousands of returned

objects, archives being opened to researchers

and an online database connecting collections

and heirs. While he’s grateful for every object

restituted under the Washington Principles, he still

experiences backlash and outright refusal by some

institutions.

Mr Eizenstat was serving as Ambassador to the

European Union when he was negotiating the

treaty in 1998, leading to thousands of returned

objects, archives being opened to researchers

and an online database connecting collections

and heirs. While he’s grateful for every object

restituted under the Washington Principles, he still

experiences backlash and outright refusal by some

institutions. Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic “The Watzmann” was owned by Jewish art

collector Martin Brunn, he sold it in 1937, hoping to finance his family’s escape to

the United States. The proceeds were forfeited, though, under a decree called the

“Reich Flight Tax”, an especially perverted way for the Nazis to expropriate anyone

trying to escape violence and persecution.

Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic “The Watzmann” was owned by Jewish art

collector Martin Brunn, he sold it in 1937, hoping to finance his family’s escape to

the United States. The proceeds were forfeited, though, under a decree called the

“Reich Flight Tax”, an especially perverted way for the Nazis to expropriate anyone

trying to escape violence and persecution. One of the biggest beneficiaries of the confiscation

of art all over Nazi Germany was Hermann

Göring, whose country residence Carinhall was

filled with objects acquired under, at best, dubious

circumstances. The buildings were razed during

the last days of the war, only rubble and the

former guard towers remain. Even the signpost

pinpointing the exact location is frequently painted

over.

One of the biggest beneficiaries of the confiscation

of art all over Nazi Germany was Hermann

Göring, whose country residence Carinhall was

filled with objects acquired under, at best, dubious

circumstances. The buildings were razed during

the last days of the war, only rubble and the

former guard towers remain. Even the signpost

pinpointing the exact location is frequently painted

over. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s blue etching “Fehmarnhäuser mit großem Baum” belonged to

Eugen Moritz Buchthal, who was forced to sell it to afford the Reich Flight Tax. He and his

family succesfully emigrated to London, the etching was among nine restituted in August

2017.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s blue etching “Fehmarnhäuser mit großem Baum” belonged to

Eugen Moritz Buchthal, who was forced to sell it to afford the Reich Flight Tax. He and his

family succesfully emigrated to London, the etching was among nine restituted in August

2017. Another story of expropriation, displacement and the impossibility of adequate reparations

is that of Agathe and Ernst Saulmann. Travelling to rural Southwest Germany to find

out more about them, we could still feel the prejudice and mentality that lead to their

expulsion. Us visiting the remainders of their live in Pfullingen lead to raised eyebrows

among some of the local population, more than 80 years after the fact.

Pictured is the factory they owned until 1936, when it was auctioned off and the proceeds

forfeited under the Reich Flight Tax.

Another story of expropriation, displacement and the impossibility of adequate reparations

is that of Agathe and Ernst Saulmann. Travelling to rural Southwest Germany to find

out more about them, we could still feel the prejudice and mentality that lead to their

expulsion. Us visiting the remainders of their live in Pfullingen lead to raised eyebrows

among some of the local population, more than 80 years after the fact.

Pictured is the factory they owned until 1936, when it was auctioned off and the proceeds

forfeited under the Reich Flight Tax. Agathe and Ernst Saulmann fled to France,

where they were eventually arrested and sent

to a concentration camp. Ernst succumbed to

the injuries sustained during their incarceration,

while Agathe commited suicide after returning to

Germany. She was never to set foot onto their vast

property with the impressive driveway again.

One object of their confiscated art collection

ended up in the collection of the Bode museum

and was restituted in 2017, just to be bought back

immediately by the museum, where it is currently

on display.

Agathe and Ernst Saulmann fled to France,

where they were eventually arrested and sent

to a concentration camp. Ernst succumbed to

the injuries sustained during their incarceration,

while Agathe commited suicide after returning to

Germany. She was never to set foot onto their vast

property with the impressive driveway again.

One object of their confiscated art collection

ended up in the collection of the Bode museum

and was restituted in 2017, just to be bought back

immediately by the museum, where it is currently

on display. This salt container was one of many decorative arts pieces in the collection of Margarethe

Oppenheim. Her heirs auctioned it off in 1935 and it remains unclear wether they were

able to keep the proceeds or were pressured by the Nazis to sell the collection as quickly

as possible, leading to a settlement with the museum being allowed to keep some of the

pieces.

The Christian relief on the right, from 1440, showing the bearing of the cross, belonged to Harry Fuld

jun., who fled from persecution in 1936 and left it in storage. It was subsequently seized

and sold to the Berlin museums. After being restituted in 2009, a foundation bought it

back, allowing it to be kept on display at the Bode Museum.

This salt container was one of many decorative arts pieces in the collection of Margarethe

Oppenheim. Her heirs auctioned it off in 1935 and it remains unclear wether they were

able to keep the proceeds or were pressured by the Nazis to sell the collection as quickly

as possible, leading to a settlement with the museum being allowed to keep some of the

pieces.

The Christian relief on the right, from 1440, showing the bearing of the cross, belonged to Harry Fuld

jun., who fled from persecution in 1936 and left it in storage. It was subsequently seized

and sold to the Berlin museums. After being restituted in 2009, a foundation bought it

back, allowing it to be kept on display at the Bode Museum. Michaela Scheibe is a historian working for the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin, focussing mostly

on provenance research and the subsequent restitution of books. A monumental task,

considering there are more than three million books in the collection of the library alone.

And while the restitution of famous paintings tends to make the news, books are often

of little value, with some of the heirs of the owners not even interested in having them

returned.

Michaela Scheibe is a historian working for the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin, focussing mostly

on provenance research and the subsequent restitution of books. A monumental task,

considering there are more than three million books in the collection of the library alone.

And while the restitution of famous paintings tends to make the news, books are often

of little value, with some of the heirs of the owners not even interested in having them

returned. To find books that might be acquired through

confiscation or expropriation, she goes through the

acquiration logs of the Nazi years and flags any

books of dubious provencance. Those will then be

taken from storage and manually checked for any

hints leading to their previous owners.

To find books that might be acquired through

confiscation or expropriation, she goes through the

acquiration logs of the Nazi years and flags any

books of dubious provencance. Those will then be

taken from storage and manually checked for any

hints leading to their previous owners. Hans von Marée’s “Self Portrait with Yellow Hat” was part of probably the most extensive

and important private collection in Europe at the time, that of Max Silberberg. He was

systematically expropriated, his company “Aryanized” and lived in poverty up until his

murder in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

The painting was the first to be restituted under the Washington Principles, in 1999, more

than 60 years after it was robbed by the Nazis.

Hans von Marée’s “Self Portrait with Yellow Hat” was part of probably the most extensive

and important private collection in Europe at the time, that of Max Silberberg. He was

systematically expropriated, his company “Aryanized” and lived in poverty up until his

murder in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

The painting was the first to be restituted under the Washington Principles, in 1999, more

than 60 years after it was robbed by the Nazis.